The Raw Beauty of Brutalism

Not so long ago, Brutalism fell out of favour for being too brutal, too harsh and even too ‘socialist’. A style of architecture that originated in England in the 1950s, it lasted well into the 1970s and some even argue that elements of this stark, monolithic approach can even be seen in the work of Le Corbusier as early as the late 1940s. Once highly popular and seen as the answer to a pressing housing shortage, particularly after World War Two, Brutalism became the favoured style for many institutional buildings before becoming derided and even vilified for many years. Nowadays, however, it has finally come back in from the cold; you could even say that it’s enjoying something of a revival.

Vintage Brutalist Handcrafted Pottery Vase with geometric design AU

Materials used in Brutalist Art

Construction, materials, and textures: these are the three components that Brutalism favours and consequently, the style probably brings to mind reinforced concrete, steel and modular elements in geometric designs. The institutional element of its use also means that the scale of the architecture renders it imposing, as larger, public buildings were often created out of gigantic blocks of concrete, size emphasised all the more by minimalist, impenetrable design.

Vintage Brutalist Vase AU

Brutalism, surprisingly, doesn’t get its name from the ‘brutal’ appearance of its creations, but instead from the material without which it couldn’t exist: béton brut, raw concrete. Unfortunately, raw concrete does not stand the test of time well and its aesthetic can be compromised by damage and decay. It was partly as a result of this and also, a rather austere, cold nature that made so many turn their backs on the architecture. At present, Brutalism’s graphic nature has once again started to appeal to people; new projects have gained momentum and are underway. It’s been suggested that perhaps, in an uncertain world, people are once more embracing the solidity and uncompromising shapes of the style.

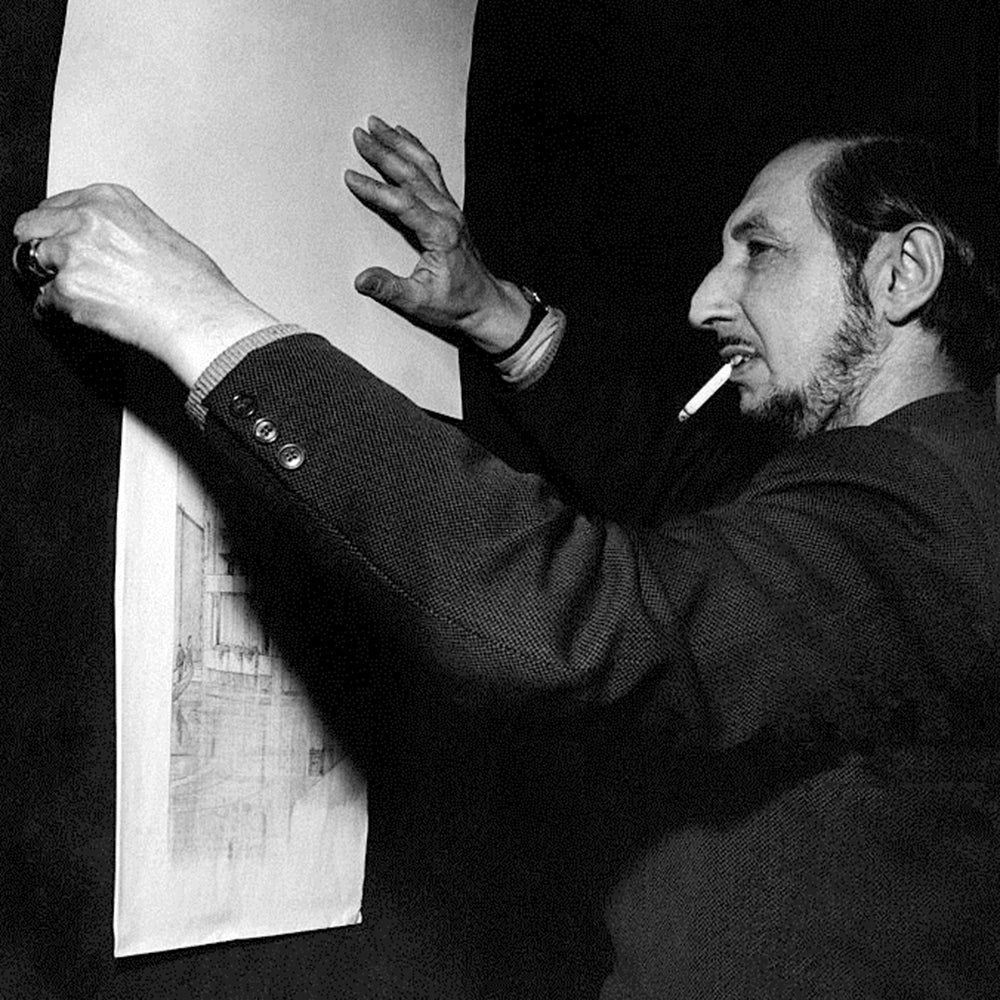

Brutalism has lent its name to much more than architecture. The term ‘Art brut’ – literally ‘raw art’ – was coined by the French artist Jean Dubuffet to describe art such as graffiti, which is highly expressive, but conceived and made outside the usual academic tradition of fine art.

The ‘Art brut’ movement

The ‘Art brut’ movement postulated that not only could anything at all be used to create a work of art, whether that was rusty metal or a kitchen object, but also, that artists with no formal training whatsoever could and should still be recognised for their primitive talent and artistic insight. This included those whose endeavours had previously been dismissed, such as children, prisoners and even, the insane. Essentially, ‘Art Brut’ gives prominence to the visual representation of emotions and feelings, expressed unhindered or constrained by rigid convention. And can anything be less brutal than the inclusivity of an art form that is only interested in the unrefined emotion of the creator and the materials they happen to have at hand rather than whether they have attended art school?

Many pieces of art, craftwork, furniture and ceramics produced during the twentieth century have been called ‘Brutalist’. Although there are no specific criteria for such a label, objects have been identified in this way, not only because of the roughness or coarseness of the material from which they were handcrafted, but also because of their functionality; their beauty growing directly as a result of daily use.

Vintage Brutalist Ceramic Hand Thrown Table Lamp AU

Most are one off pieces borne out of an intuitive and instinctive design process, purposefully lacking conspicuous aesthetics and more overt polish. And it is a contrast inherent in the pieces - obviously finished, sometimes ostentatious, but seemingly roughly hewn and somewhat untamed - which makes them so captivating; it lends an authenticity that is unpredictable and therefore all the more desirable for its wild fearlessness.

To browse AU’s collection, please click here.

Continue reading